Cosmogonic relationship between the cenotes of southeastern Mexico and the jagüeyes of the Mexican highlands: a response to sustainable agricultural development.

By Mtra. Angélica Muñoz Martín, Arq. Sugey Rendón Valencia y Dra. María Guadalupe Valiñas Varela

Cultural Exchange through Trade Migrations between Yucatán and Hidalgo

Topic: Sustainable Development

The Central Highlands of Mexico are characterized by a dry and extreme climate, a result of its high altitude. Rainfall varies across the region, causing periods of both humidity and drought. During the day, temperatures can be high, while nights are cold, creating a semi-desert environment that influences vegetation and human activities. The warm season is characterized by intense heat and dryness, while winters are cold and the rains are concentrated in the summer. This climate pattern restricts water availability, which has led to the adaptation of xerophytic vegetation such as cacti and drought-resistant shrubs, and the implementation of advanced irrigation techniques to sustain agriculture in these adverse conditions (Narváez, 2016).

In contrast, southern Mexico has a tropical climate with abundant rainfall year-round. High humidity and warm temperatures favor lush vegetation, including rainforests and tropical forests, contributing to rich biodiversity. This tropical climate allows for the cultivation of crops such as corn, cacao, and coffee, which thrive in these conditions. The abundance of water in the south not only supports diverse agriculture but also ensures the stability of the local ecosystem and the protection of water resources, contributing to a shared understanding of our place in the world (Bautista, 2021).

Worldview, cosmogony, and cosmology offer different perspectives on the universe. A worldview is the way individuals and societies interpret reality and the cosmos, influenced by cultural, historical, and philosophical beliefs. This holistic view affects the perception of natural phenomena, existential principles, and the purpose of life, impacting daily practices and decisions. It reflects the diversity of human experiences. Cosmology, a branch of astronomy, studies the universe in its entirety, including its origin, evolution, and current and future structure, using theoretical models and observations. Cosmologists explore the model of cosmic inflation to build a mathematical understanding of the cosmos. In contrast, cosmogony examines narratives about the origin and structure of the universe. In ancient times, mythological cosmogonies recounted creation through supernatural beings. (Gámez Espinosa & Austin 2015)

In the context of Mesoamerican cultures, it is crucial to distinguish between the terms Nahua, Náhuatl, and Mexica. "Nahua" is a broad term that encompasses indigenous peoples who speak languages from the Uto-Aztecan family, including communities such as the Mexica, Tlaxcalans, and Pochtecas. This term encompasses diverse cultural and linguistic identities. "Nahuatl" refers specifically to the language spoken by the Nahuas, which is fundamental to interpreting pre-Hispanic documentation and literature and is still spoken by indigenous communities in Mexico. On the other hand, "Mexica" designates the specific group within the Nahuas that founded the empire that dominated much of central Mexico before the arrival of the Spanish. It is distinguished by its influence on history, architecture, religion, and social organization.

The Mexica worldview regarding water reveals how these cultures valued water not only as a vital resource, but also as a sacred element. In the Mexica worldview, water played a fundamental role in the creation of the world and in daily life. Energies such as Tlaloc-Huitzilopochtli and Chalchiuhtlicue underscored the importance of water in the recognition of daily life. Water was crucial for agriculture and survival, and its role in cultic practices underscored its status as an important element. (Valle Cedano 2013)

Water management was essential for the city-states of pre-Hispanic Mexico. Jagüeyes and cenotes were vital for water supply in regions with irregular seasonal rainfall. Jagüeyes are dug and lined wells used to store rainwater, essential in dry or semi-arid regions for agriculture and community (Ruíz). Cenotes, geological formations in karst regions such as the Yucatán Peninsula, were formed by the collapse of caves due to the dissolution of limestone, offering accessible water reservoirs and playing a crucial role in both water management and cultural processes. (Espino 2018)

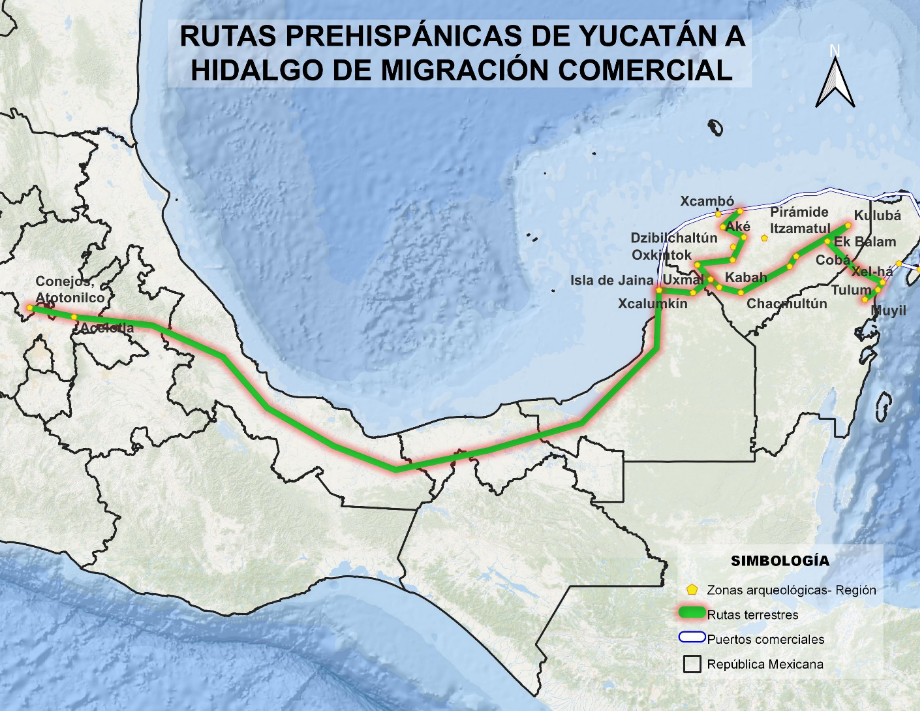

Pre-Hispanic commercial migration between Hidalgo and Yucatán represents a key phenomenon in the regional development of the Americas. This exchange of goods and knowledge, facilitated by traders, connected distant regions through routes that integrated Hidalgo's agricultural wealth with Yucatán's mineral and cultural resources. The flow of products such as cacao, jade, and textiles, along with the transfer of agricultural technologies and artisanal techniques, strengthened the economy and social cohesion in both regions, promoting regional stability and cultural interaction (Cossens 2019).

One of the greatest examples of this is the relationship between the jagüey of Hidalgo and the cenote of Yucatán.

Figure 1. Natural jagüey, Conejos Atotonilco de Tula, Hidalgo. Photo by Mtra. Muñoz, Sep. 2024

Figure 2. Constructed jagüey, Acelotla Zempoala, Hidalgo. Photo by Mtra. Muñoz, Sep. 2024

Yucatan's cenotes, sacred rainforests, are true natural treasures that store the precious resource of water. These places of protection, surrounded by the majesty of nature, contrast with the depth of the dark caves and the clarity of the clear skies. In these underground spaces, the daily work of agriculture is elevated to an almost sublime level, where the beauty of the surroundings enhances human effort.

Figure 3. Natural cenote Chichen Itzá. Photo by Mtra. Muñoz. July 2024

Figure 4. Artificial cenote Los Cochitos Progreso. Photo by Mtra. Muñoz. July 2024

Commercial migrations, driven by the need to find unknown objects from the central regions, led the inhabitants to discover the wonders of Yucatán, a paradise that remained hidden from them. In contrast to the arid central highlands, where vegetation was sparse and vibrantly colored birds were only a dream, encountering the cenotes offered a completely new perspective.

In the highlands, great warriors farmed painstakingly in arid lands, using only jagüeyes—temporary, excavated and lined water containers—to manage water resources. However, when some of these warriors ventured into the Yucatán, they brought the vision of the cenotes with them to their brothers in what is now Hidalgo. There, the wonders of the cenotes were shared, and the jagüeyes adapted to solve the challenge of water in low-filtration regions. Through the technique of water harvesting and protection, they improved agriculture, transforming seasonality into a more stable and lasting agricultural system, greening the places and beautifying their lives to this day.

Figure 5. Trade route from Yucatán to Hidalgo, connecting Jagüeyes and archaeological sites. Map by Architect Rendon, supported by DIGITAL MAP. Roberto Sánchez, Lorena Rugerio. INEGI

REFERENCES:

Alejandra [VNV] Gámez Espinosa, & Austin, A. L. (2015). Cosmovisión mesoamericana: reflexiones, polémicas y etnografías. FCE, COLMEX, FHA, BUAP.

Bautista. (2021). Los territorios kársticos de la península de Yucatán: caracterización, manejo y riesgos [Digital]. Acts With Science, S. de R.L. de C.V. ISBN: 978-607-97684-2-3. Pp.10-12b

Cossens, S. (2019). Rutas comerciales en Mesoamérica: la formación del sistema internacional prehispánico. Revista de Relaciones Internacionales de la UNAM. Pp. 9-12

Espino, D. L. A. (2018) Las cavernas dentro de la visión maya yucateca de ayer y hoy. Diario de Campo, pp.3

Narváez Suárez, A. U., Martínez Saldaña, T., & Jiménez Velázquez, M. A. (2016). El cultivo de maguey pulquero: opción para el desarrollo de comunidades rurales del altiplano mexicano. Revista de Geografía Agrícola, (56), pp.6-9.

Ruiz, J. L. M. Los verdaderos dueños del agua y el monte. Agua en la Cosmovisión de los Pueblos Indígenas en México, pp. 184

Valle Cedano, O. (2013). Cosmovisión prehispánica: El culto al agua y al cerro en el sitio arqueológico La Malinche, Tenancingo, Estado de México.

Zárate, B. A. A. (1997). Graniceros: cosmovisión y meteorología indígenas de Mesoamérica. Unam. Pp.23-47